The post Cultivating New Leaders, Healthier Futures through Family Gardens appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>With support from the United States Agency for International Development’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA), through the Honduras Agricultural System Support (HASS) program, Glendy has seen her life flourish in ways she never anticipated. And it all started with a family garden.

Before participating in the HASS program, Glendy had to travel almost 14 miles to the nearest town to buy produce. Now, thanks to resources and training she received through HASS, a variety of fresh vegetables are literally at her fingertips. Every morning, she and her family get up early to water and take care of the land. With the daily harvest, Glendy is able to feed her children in a healthier and more sustainable way, significantly improving their quality of life and future.

Before, we had to wait for a car to come to the community once a week to buy vegetables or make a trip to the town. But since I have the family garden, I have fresh vegetables every day.”

Glendy, HASS program participant

In addition to improving her household’s nutrition, Glendy uses the leftover harvest from her garden to earn extra income. She sells the produce to community members and even inspired other women with gardens to follow her example. Together, they created a messaging group that allows them to coordinate sales to meet the area’s demand. With the income generated from these sales, Glendy purchased a variety of seeds to diversify her garden. Now, she grows everything from carrots and tomatoes to cucumbers, onions, green beans and radishes. Profits have also enabled her to cover her children’s school expenses.

Access to resources such as home gardens is especially significant for women, as it opens up new opportunities for entrepreneurship, income generation and family support.

In this sense, Glendy’s leadership and initiative did not go unnoticed. Her commitment and skills led to her selection as a volunteer agricultural collaborator with the HASS program. In this role, she advises and supports other small-scale farmers, ensuring they correctly apply the techniques learned during training. She also provides guidance on crop management, among other tasks.

Glendy says this new role has empowered her and changed the trajectory of what she believes is possible for her life. She is motivated to continue her studies, convinced that education will open up new opportunities and guarantee a better future for her and her family. For Glendy, it’s not just about achieving her own goals but about being an example for her children. She wants them to grow up knowing that, with hard work and dedication, it is possible to change the course of their lives.

“My greatest satisfaction is to hear my children tell me they are proud of what I have achieved,” she says. “Also, thanks to this project, I was able to discover the leader inside me. People in my community now recognize me, and there are other organizations that have approached me to support them.”

Since working as a volunteer agricultural collaborator, Glendy has had the opportunity to manage clean-up campaigns, exchange seeds among the women who have gardens, and inspire others to transform their dreams into achievable realities. Organizations outside of the HASS program have even offered her internships to strengthen her skills as a community leader. Her dedication and success are a prime example of how women — when given the right opportunities and resources — can transform their lives through agricultural work and entrepreneurship.

The post Cultivating New Leaders, Healthier Futures through Family Gardens appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post María’s Harvest: Empowering Sustainable Farming and Drought Resilience in Honduras appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>“This is the first time that a project has come to the community to provide training to improve farming techniques,” shares María. “Before, we managed to produce six loads of corn and now, we manage 14. We did not plant any beans before [the HASS project] and now, we harvest four loads because we learned how to take advantage of the land. Thanks to USAID/BHA, we now have guaranteed food for a longer time.”

Through HASS, project participants like María are putting into practice what they have learned. They have planted a variety of crops such as beans, radish, sweet chili, cucumber, squash and mustard. Crop diversification for self-consumption is a key strategy to improve the nutrition of communities by providing a greater variety of nutrients, reducing the risk of deficiencies and promoting healthier diets.

Integration of sustainable agricultural practices

HASS promotes food security, encourages learning sustainable agricultural practices and strengthens producer’s knowledge through targeted project implementation strategies. The integration of agricultural practices carried out by HASS works to improve food security, provide access and facilitate food for families. HASS trainings include agricultural technologies, technical assistance, delivery of agricultural materials, tools and equipment for the establishment of family gardens, drip irrigation systems and water harvesting with geomembrane bags.

An alternative method for the dry season

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the first half of 2024 is expected to be impacted by the El Niño phenomenon – a weather event marked by warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures – creating prolonged droughts. In the upcoming months, the impact of the La Niña phenomenon is expected to put small-scale production of basic grains at risk in the Honduran Dry Corridor (CSH).

Without the added complication of the El Niño phenomenon, María faces water shortages during the dry season. To meet her family’s domestic need for water, they temporarily connect hoses from the beginning of a creek to their homes. However, this solution does not meet the additional water requirements to irrigate her garden. Aware of the importance of keeping the harvester full, María and her family have explored alternatives, they organize themselves to carry water in containers to ensure the supply of the vital liquid.

To help reduce the impact of the dry season, Global Communities with support from USAID/BHA, is installing water harvesters with geomembrane bags for small-scale producers in supported communities. With these water harvesters, they can maintain a constant supply of water for irrigation of their home gardens. This equipment collects rainwater through a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) drain installed on the roof of the house. Once collected, the water is stored in a highly resistant geomembrane bag where it is kept until it is used to irrigate crops. Knowing that water will be available helps farmers navigate the increasingly unpredictable planting cycles in the Dry Corridor.

263 water harvesters will be installed across different communities in the Honduran Dry Corridor through the HASS project.

These harvesters represent an innovative and efficient solution to capture and store water in areas where the resource is limited. This allows project participants to collect and retain rainwater effectively, offering an opportunity for communities and families facing water shortages.

“My commitment is to take care of this water harvester so that it will last me a long time,” said María.

In these CSH communities, water harvesters emerge as a ray of hope, as a tool that guarantees crops’ survival and represents the communities’ symbol of resistance and resilience.

The post María’s Harvest: Empowering Sustainable Farming and Drought Resilience in Honduras appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post Adapting and Innovating in a Volatile World: Reflections from the 2024 Fragility Forum appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>

Last month, the World Bank held its 2024 Fragility Forum – a biannual conference that brings together policymakers, researchers and practitioners from humanitarian, development and peacebuilding communities to exchange knowledge and ideas about how to improve our approaches in fragile, conflict and violence-affected settings. This year’s theme was “Adapting and Innovating in a Volatile World.”

After the Forum, I asked my Global Communities’ colleagues who attended the event for their reflections. Kelly Van Husen, Vice President for Humanitarian Assistance; Patricia Dorsher, Senior Manager for Humanitarian Business Development; Meena Grigat, Director of Humanitarian and Nexus Business Development; and Patrick Woodruff, Manager for Humanitarian Assistance participated in the exchange. The conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Paula: In most of the sessions I attended, the panelists painted a bleak picture. The world is increasingly fragile, marred with compounded crises and intertwined risks, from protracted conflicts and climate disasters to chronic political instability and widespread food insecurity. The World Bank estimates that by 2030, almost 60% of the world’s poor will live in countries classified as fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS). During the opening session, Anna Bjerde, Managing Director of Operations at the World Bank noted that we cannot end poverty without addressing fragility. She also said, “I’m going to be very honest with you. … We are not preventing conflict.” Why? What are the key factors behind these alarming trends?

Patricia: I have been working on our humanitarian assistance portfolio for the past few years and found it difficult to identify funders who are willing to address the root causes of conflict in contexts like Syria, where the outcomes are very political. For example, investing in infrastructure in the non-regime areas could help stabilize the lives for millions of people, but humanitarian donors do not see this as their purview and development actors do not want to pay for something where there is no recognized government counterpart to work with. We have been working to find intermediate solutions, but with funds decreasing, humanitarian donors want to focus on the urgent, lifesaving activities and not those that can help counter systemic fragility.

Patricia: I have been working on our humanitarian assistance portfolio for the past few years and found it difficult to identify funders who are willing to address the root causes of conflict in contexts like Syria, where the outcomes are very political. For example, investing in infrastructure in the non-regime areas could help stabilize the lives for millions of people, but humanitarian donors do not see this as their purview and development actors do not want to pay for something where there is no recognized government counterpart to work with. We have been working to find intermediate solutions, but with funds decreasing, humanitarian donors want to focus on the urgent, lifesaving activities and not those that can help counter systemic fragility.

Patrick: Well said, Patricia. Humanitarian and development organizations are often forced to choose between working with actors considered illegitimate by the international community and restricting or even halting programming to at-risk populations. This was evident after the Taliban’s takeover in Afghanistan. The disengagement of many actors, including donors, not only left many people at increased risk, but resulted in brain drain of trained humanitarian workers who fled the country or went underground. The lack of funding and support for national non-governmental organizations has led to devastating backtracking on hard-won gains in the rights of women and minority groups. We can see this trend in almost every major crisis today, from Ukraine and Syria to Gaza and the West Bank. Furthermore, many, if not most humanitarian and development organizations are overly reliant on government funding from the Global North. It makes it increasingly difficult to respond to the needs on the ground when the donor countries are aligned with one side of a conflict. While this is understandable from a political standpoint, porous funding streams leave hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people without lifesaving aid, in direct contradiction to the humanitarian principles.

Patrick: Well said, Patricia. Humanitarian and development organizations are often forced to choose between working with actors considered illegitimate by the international community and restricting or even halting programming to at-risk populations. This was evident after the Taliban’s takeover in Afghanistan. The disengagement of many actors, including donors, not only left many people at increased risk, but resulted in brain drain of trained humanitarian workers who fled the country or went underground. The lack of funding and support for national non-governmental organizations has led to devastating backtracking on hard-won gains in the rights of women and minority groups. We can see this trend in almost every major crisis today, from Ukraine and Syria to Gaza and the West Bank. Furthermore, many, if not most humanitarian and development organizations are overly reliant on government funding from the Global North. It makes it increasingly difficult to respond to the needs on the ground when the donor countries are aligned with one side of a conflict. While this is understandable from a political standpoint, porous funding streams leave hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people without lifesaving aid, in direct contradiction to the humanitarian principles.

Patricia: So true! During the session on “State Building in Protracted Crises,” I was struck by the discussion on Palestine led by Nigel Roberts, former Country Director for Gaza and the West Bank at the World Bank. Roberts talked about how the World Bank is designed to be apolitical – at least at a technocratic level – but is beholden to a board that is, by nature, political. Because of this dichotomy, the World Bank has missed many opportunities to help realize economic improvements and development objectives for Palestinians. This resonated with me. In humanitarian assistance, we frequently grapple with the mandate to be “neutral” and “apolitical,” and yet our largest government donors are responsible for carrying out domestic and foreign policies. Being neutral or apolitical is often thought of as the refusal to choose sides, but we fail to recognize that this is also a choice with consequences. It raises the question of what it means to be neutral or apolitical, and if it is ever truly possible.

Patricia: So true! During the session on “State Building in Protracted Crises,” I was struck by the discussion on Palestine led by Nigel Roberts, former Country Director for Gaza and the West Bank at the World Bank. Roberts talked about how the World Bank is designed to be apolitical – at least at a technocratic level – but is beholden to a board that is, by nature, political. Because of this dichotomy, the World Bank has missed many opportunities to help realize economic improvements and development objectives for Palestinians. This resonated with me. In humanitarian assistance, we frequently grapple with the mandate to be “neutral” and “apolitical,” and yet our largest government donors are responsible for carrying out domestic and foreign policies. Being neutral or apolitical is often thought of as the refusal to choose sides, but we fail to recognize that this is also a choice with consequences. It raises the question of what it means to be neutral or apolitical, and if it is ever truly possible.

Paula: How can we, and others in the sector, address these challenges?

Patrick: To me, some of the most impactful discussions at the Fragility Forum were around the need to stay engaged in challenging situations, including by finding ways to work with illegitimate or diplomatically isolated actors. Many panelists emphasized that humanitarian organizations have the moral responsibility to remain engaged in order to alleviate suffering. They also noted that continued engagement decreases the financial and social costs that result from humanitarian and development actors leaving in the face of these challenges. Of course, there is no easy solution to this, and every organization needs to make its own decisions based on acceptable risk levels. I think that the most important thing that organizations can do is to protect the foundations of humanitarian work, which is rooted in the principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence. By reinforcing these ideals, organizations will be better positioned to respond to crises based on needs.

Patrick: To me, some of the most impactful discussions at the Fragility Forum were around the need to stay engaged in challenging situations, including by finding ways to work with illegitimate or diplomatically isolated actors. Many panelists emphasized that humanitarian organizations have the moral responsibility to remain engaged in order to alleviate suffering. They also noted that continued engagement decreases the financial and social costs that result from humanitarian and development actors leaving in the face of these challenges. Of course, there is no easy solution to this, and every organization needs to make its own decisions based on acceptable risk levels. I think that the most important thing that organizations can do is to protect the foundations of humanitarian work, which is rooted in the principles of impartiality, neutrality and independence. By reinforcing these ideals, organizations will be better positioned to respond to crises based on needs.

Meena: The sessions I listened to reinforced the importance of investing time and resources into developing an in-depth understanding of the local context. It is very important to build long-term relationships with local communities and actors, and to conduct political economy and conflict analyses. We must be ready to work with communities and local systems over the long-term in order to see impact.

Meena: The sessions I listened to reinforced the importance of investing time and resources into developing an in-depth understanding of the local context. It is very important to build long-term relationships with local communities and actors, and to conduct political economy and conflict analyses. We must be ready to work with communities and local systems over the long-term in order to see impact.

Patricia: I have to echo what Meena said. You can’t ignore the political context and conflict dynamics. Understanding them at the macro, meso, micro and even household levels is essential if we want to work effectively in fragile and conflict-affected areas. I also want to second what Patrick said about staying engaged. When a new crisis emerges, donors and implementers cannot just forget about conflicts that have been going on for years or decades. When Russia invaded Ukraine, there was a sudden reassignment of critical funding and programming to Ukraine and its refugees. Now, the devastating humanitarian crisis in Gaza dominates the headlines. While we must respond to these new crises to the fullest extent possible, we must still remember about people in Yemen, Syria and other fragile states with protracted conflicts and instability. Their voices deserve to be heard, and their needs deserve to be met, too. I am proud of our programming in Syria, where we have been addressing food security, protection, water, sanitation and shelter needs for a decade. I truly hope donors will remain engaged there for years to come.

Patricia: I have to echo what Meena said. You can’t ignore the political context and conflict dynamics. Understanding them at the macro, meso, micro and even household levels is essential if we want to work effectively in fragile and conflict-affected areas. I also want to second what Patrick said about staying engaged. When a new crisis emerges, donors and implementers cannot just forget about conflicts that have been going on for years or decades. When Russia invaded Ukraine, there was a sudden reassignment of critical funding and programming to Ukraine and its refugees. Now, the devastating humanitarian crisis in Gaza dominates the headlines. While we must respond to these new crises to the fullest extent possible, we must still remember about people in Yemen, Syria and other fragile states with protracted conflicts and instability. Their voices deserve to be heard, and their needs deserve to be met, too. I am proud of our programming in Syria, where we have been addressing food security, protection, water, sanitation and shelter needs for a decade. I truly hope donors will remain engaged there for years to come.

Kelly: One theme that I heard repeatedly in the sessions I attended was around the need to be agile and innovative. This is not necessarily new, but the speakers highlighted how critical it is for implementers – particularly those working in fragile contexts – to be flexible: constantly evaluating, assessing and identifying new opportunities to shift programming to better meet humanitarian needs and more effectively achieve program outcomes. The Forum also reinforced the need for continued advocacy to our donors, policymakers and other stakeholders around flexible funding mechanisms. In a volatile world we live in, funding mechanisms must have built-in opportunities, such as crisis modifiers, to quickly adapt and pivot to rapid emergency response.

Kelly: One theme that I heard repeatedly in the sessions I attended was around the need to be agile and innovative. This is not necessarily new, but the speakers highlighted how critical it is for implementers – particularly those working in fragile contexts – to be flexible: constantly evaluating, assessing and identifying new opportunities to shift programming to better meet humanitarian needs and more effectively achieve program outcomes. The Forum also reinforced the need for continued advocacy to our donors, policymakers and other stakeholders around flexible funding mechanisms. In a volatile world we live in, funding mechanisms must have built-in opportunities, such as crisis modifiers, to quickly adapt and pivot to rapid emergency response.

Paula: Indeed. The ability to fluidly respond to changing circumstances is a game changer. We have witnessed how crucial this is in many contexts. In Ukraine, for example, our long-term development program – Decentralization Offering Better Results and Efficiency (DOBRE) – was able to quickly mobilize its networks and provide rapid emergency response right at the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. This paved a way for the Community-Led Emergency Action and Response (CLEAR) program, which we launched soon after in two regions overlapping with DOBRE. By layering life-saving humanitarian interventions with development assistance, we can more effectively respond to the crisis, set the stage for post-war recovery and foster lasting resilience to shocks and stresses.

Paula: Indeed. The ability to fluidly respond to changing circumstances is a game changer. We have witnessed how crucial this is in many contexts. In Ukraine, for example, our long-term development program – Decentralization Offering Better Results and Efficiency (DOBRE) – was able to quickly mobilize its networks and provide rapid emergency response right at the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. This paved a way for the Community-Led Emergency Action and Response (CLEAR) program, which we launched soon after in two regions overlapping with DOBRE. By layering life-saving humanitarian interventions with development assistance, we can more effectively respond to the crisis, set the stage for post-war recovery and foster lasting resilience to shocks and stresses.

Ethiopia also comes to mind, where we are implementing the Resilience in Pastoral Areas South (RIPA South) project. In March 2022, amid one of the driest rainy seasons on record, RIPA South activated a Crisis Modifier to address urgent needs of the most vulnerable people affected by the drought. The Crisis Modifier sets aside funds for emergency response measures to save people’s lives, rescue livestock and safeguard economic gains made possible by development activities. We have categorized these interventions into three windows: livestock support, multi-purpose cash assistance and access to water, sanitation and hygiene.

Paula: Where else is Global Communities adapting or innovating in the face of fragility and constant change?

Kelly: Gaza was mentioned several times during the Forum. Since the start of the Israel-Hamas war on October 7, 2023, we have pivoted more than 20 years of programming to address the urgent needs resulting from this devastating humanitarian crisis. Our teams are managing to adapt and innovate in Gaza, despite extremely constrained and dangerous circumstances. As you know, 2.2 million people are at the imminent risk of famine, and we are proud to serve as the World Food Programme’s (WFP) main implementing partner. We have been able to shift our WFP work from cash to in-kind assistance, and we have pooled resources and knowledge to partner with others, for example the World Central Kitchen, to provide hot meals. We are also distributing nutritional supplements to pregnant women, nursing mothers and small children who are at increased risk of malnutrition. In addition, we are setting up latrines and sinks, and he have provided winterization support to many families. This represents critically needed agility and creativity that has enabled us to continue working in this extremely challenging environment.

Kelly: Gaza was mentioned several times during the Forum. Since the start of the Israel-Hamas war on October 7, 2023, we have pivoted more than 20 years of programming to address the urgent needs resulting from this devastating humanitarian crisis. Our teams are managing to adapt and innovate in Gaza, despite extremely constrained and dangerous circumstances. As you know, 2.2 million people are at the imminent risk of famine, and we are proud to serve as the World Food Programme’s (WFP) main implementing partner. We have been able to shift our WFP work from cash to in-kind assistance, and we have pooled resources and knowledge to partner with others, for example the World Central Kitchen, to provide hot meals. We are also distributing nutritional supplements to pregnant women, nursing mothers and small children who are at increased risk of malnutrition. In addition, we are setting up latrines and sinks, and he have provided winterization support to many families. This represents critically needed agility and creativity that has enabled us to continue working in this extremely challenging environment.

Paula: Agility in adapting to evolving needs is vital in our efforts to ensure efficient, timely support in both stable and crisis conditions. I imagine we have had to adapt and innovate our own internal processes and mechanisms to make it happen.

Patrick: Yes, absolutely. Global Communities is currently developing Protocols for Emergency Response, so that we are humanitarian-ready even in relatively stable environments. I am personally involved in this effort. We want to ensure that our organization has systems in place to respond to natural disasters and conflicts quickly and effectively. We place a heavy focus on increasing the resilience, preparedness and ability of our country teams to respond with existing programming. This is often done by leveraging our ongoing development programs, like in Gaza, Ukraine or Ethiopia.

Patrick: Yes, absolutely. Global Communities is currently developing Protocols for Emergency Response, so that we are humanitarian-ready even in relatively stable environments. I am personally involved in this effort. We want to ensure that our organization has systems in place to respond to natural disasters and conflicts quickly and effectively. We place a heavy focus on increasing the resilience, preparedness and ability of our country teams to respond with existing programming. This is often done by leveraging our ongoing development programs, like in Gaza, Ukraine or Ethiopia.

Kelly: We work at the intersection of sustainable development and humanitarian assistance, so strenghtening the capacity of our country teams to pivot from development programming to emergency response is one of our main internal priorities.

Kelly: We work at the intersection of sustainable development and humanitarian assistance, so strenghtening the capacity of our country teams to pivot from development programming to emergency response is one of our main internal priorities.

Paula: Many panelists emphasized how important it is to strengthen local institutions and make them more inclusive in order to solve conflicts and maintain peace. For example, Bjerde said that it is crucial to focus not just on services but also on the institutions behind the services, making sure that their capacity is built. “When things go wrong, when things get difficult and hard, it’s those institutions that need to actually step up even more,” she said. What are your thoughts on this?

Patrick: I agree. This brings up the topic of localization, which was frequently mentioned at the Forum too. To protect hard fought gains, we must ensure that local and national actors – who do the vast majority of the work on the ground – have the adequate resources and power to adapt their programming in a way that is contextually appropriate.

Patrick: I agree. This brings up the topic of localization, which was frequently mentioned at the Forum too. To protect hard fought gains, we must ensure that local and national actors – who do the vast majority of the work on the ground – have the adequate resources and power to adapt their programming in a way that is contextually appropriate.

Paula: Right. Ultimately, it is the local communities and institutions who have the intimate understanding of their needs and priorities, and who can design context-specific and culturally relevant interventions. This came up a lot in the session “Gender Equality in FCV Settings: Moving from Humanitarian Responses to Creating Resilience.” Amini Kajunju from the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development spoke very passionately about investing in community-driven solutions, leveraging local expertise and elevating local women leaders. She also stressed that civil society organizations are central to providing services in fragile settings, especially when state institutions are weakened. I know that our sector has a long way to go to fully realize the localization principles, but I think we are making strides. For example, localization is a core strategy of our CLEAR project in Ukraine, where we invest in small, community-based organizations (CBOs), which deliver emergency assistance and protection services to war-affected populations. Of course, this approach has its challenges. When I visited Ukraine last year, many CBO leaders shared their struggles with strict donor compliance requirements. We hear it in other settings, like Syria, too. This is where we come in with our capacity strengthening interventions, which are extremely helpful, but take time.

Paula: Right. Ultimately, it is the local communities and institutions who have the intimate understanding of their needs and priorities, and who can design context-specific and culturally relevant interventions. This came up a lot in the session “Gender Equality in FCV Settings: Moving from Humanitarian Responses to Creating Resilience.” Amini Kajunju from the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development spoke very passionately about investing in community-driven solutions, leveraging local expertise and elevating local women leaders. She also stressed that civil society organizations are central to providing services in fragile settings, especially when state institutions are weakened. I know that our sector has a long way to go to fully realize the localization principles, but I think we are making strides. For example, localization is a core strategy of our CLEAR project in Ukraine, where we invest in small, community-based organizations (CBOs), which deliver emergency assistance and protection services to war-affected populations. Of course, this approach has its challenges. When I visited Ukraine last year, many CBO leaders shared their struggles with strict donor compliance requirements. We hear it in other settings, like Syria, too. This is where we come in with our capacity strengthening interventions, which are extremely helpful, but take time.

Paula: How else did the conference connect with the work you are doing at Global Communities?

Meena: The session “Troubled Borders: Subnational Conflict in Middle Income Countries” was relevant to the context in northern Ghana, where we have extensive experience implementing water, sanitation and hygiene programs. The region is one of the key focus areas under the U.S. Global Fragility Act. Communities in the districts along the borders of northern Ghana are part of interconnected trade and migration networks, and there are major concerns over the spread of violent extremism into these communities. The speakers stressed the complexity of border economies and governance institutions, and the need to consider market systems, the flow of goods and ideas, the role of the state, and the ability of local actors to arbitrate conflict.

Meena: The session “Troubled Borders: Subnational Conflict in Middle Income Countries” was relevant to the context in northern Ghana, where we have extensive experience implementing water, sanitation and hygiene programs. The region is one of the key focus areas under the U.S. Global Fragility Act. Communities in the districts along the borders of northern Ghana are part of interconnected trade and migration networks, and there are major concerns over the spread of violent extremism into these communities. The speakers stressed the complexity of border economies and governance institutions, and the need to consider market systems, the flow of goods and ideas, the role of the state, and the ability of local actors to arbitrate conflict.

Paula: Great point. Conflicts and the climate crisis do not recognize borders. Several panelists also emphasized the need to support countries receiving refugees and discussed the global impact of the war in Ukraine. The fragility that has emanated from Russia’s invasion has cascaded globally, affecting countries not just in Ukraine’s vicinity, but states on other continents. For example, the conflict has had a major impact on the global wheat supply, resulting in a widespread food security crisis.

Paula: Great point. Conflicts and the climate crisis do not recognize borders. Several panelists also emphasized the need to support countries receiving refugees and discussed the global impact of the war in Ukraine. The fragility that has emanated from Russia’s invasion has cascaded globally, affecting countries not just in Ukraine’s vicinity, but states on other continents. For example, the conflict has had a major impact on the global wheat supply, resulting in a widespread food security crisis.

Thank you for sharing your reflections. As some of the panelists noted, sustainable development is not possible without sustainable peace, and we need tectonic shifts and holistic approaches to address the interconnected global risks and polycrises. I left the Fragility Forum and our conversation with the following recommendations:

- Anticipate better and be prepared to ensure effective, timely support when conditions change.

- Remain engaged when challenges arise. Ensure stable funding streams. Continuity is vital when fragility grows.

- Acknowledge that conflicts and the climate crisis do not recognize borders.

- Focus on prevention and resilience building. Address the drivers and root causes of fragility.

- Strengthen state institutions, engage the private sector and invest in civil society organizations, including women- and youth-led groups, which are often first responders in fragile settings and play a huge role in recovery efforts.

- Improve governance and the rule of law.

- Ensure that interventions are inclusive and gender-responsive. Talk to people you typically do not engage with.

- Localize development and humanitarian interventions.

The post Adapting and Innovating in a Volatile World: Reflections from the 2024 Fragility Forum appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post Mother-Daughter Duo Hatch Success with Poultry Farming Business in Rural Guatemala appeared first on Global Communities.

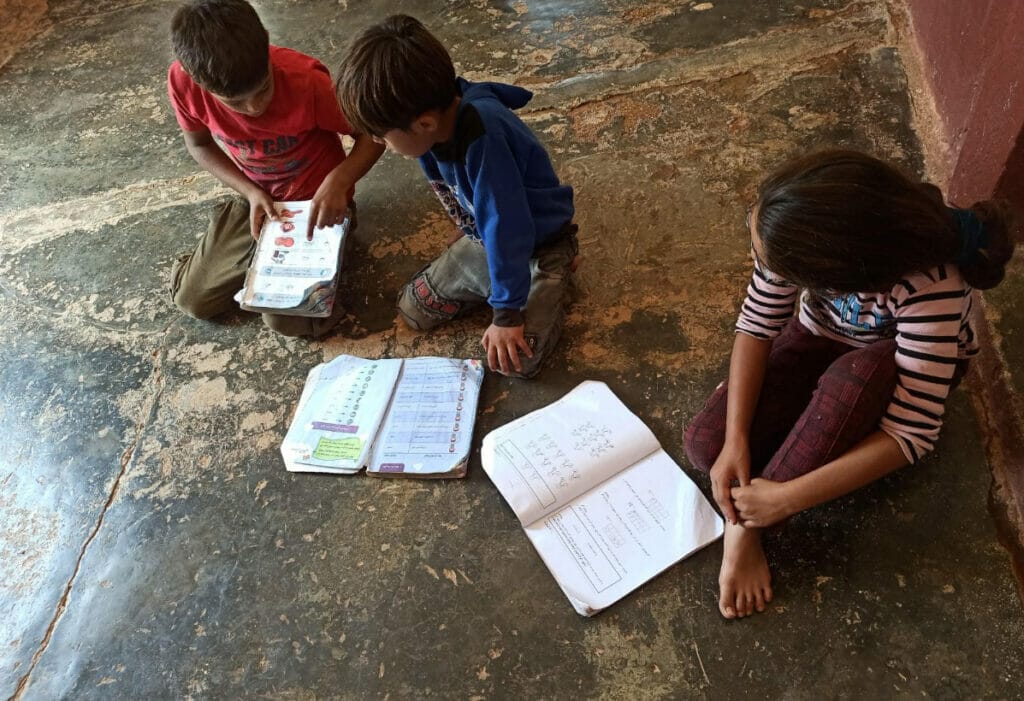

]]>As women from Pacate, a small community in the municipality of Santa Barbara, Huehuetenango, Elsa says just the opportunity to earn an income once seemed out of reach. Poverty and inequality run deep in the rural area and drive many to migrate to the city for work – a journey Elsa once undertook herself until the COVID-19 pandemic and national lockdown restrictions forced her to return home in 2020.

“[That] was one of the most difficult seasons for me,” she confides. “I only managed a few days of work washing clothes or in agriculture.”

According to the 2023 Guatemala Humanitarian Needs Overview, the humanitarian needs of vulnerable people in Guatemala increased in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. The public health crisis substantially impacted livelihoods throughout the country and led to rising prices in food and fuel. Research indicates that people living in poverty are still struggling to recover their pre-pandemic income and working conditions, with agricultural and economic losses disproportionately impacting women, particularly rural women producers. Along with the adverse economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, climate phenomena such as El Nino also have had adverse effects on grain harvests, poverty rates and nutritional risks in communities.

In January 2023, thanks to the arrival of the USAID/BHA-funded Podemos (We Can) project, Elsa saw an opportunity to change her circumstances. She expressed interest in joining Women Empowered (WE), a savings and lending group activity, and immediately became an active participant in the self-named group Mujeres Unidas (United Women). Eventually, she even took on a leadership role in the organization by managing the savings records of each of the members. She also encouraged her 23-year-old daughter, Debora, to join the group.

The mother and daughter’s main motivation for participating in the WE component of the Podemos project was to save enough money to launch a new business together. They had been weaving baskets to earn a modest income but wanted to pursue poultry farming.

“I dreamed of chickens to produce eggs and sell them,” Elsa says. “I thought that with the savings in the group, I could buy my first chickens.”

A month into project implementation, Elsa purchased 10 hens to sell eggs to a neighbor, which sparked her interest in learning more about poultry production management. After requesting and receiving technical assistance from Podemos staff, she felt motivated to expand her brood and borrowed money from her brother to buy another 52 egg-laying hens in August 2023.

“Mrs. Elsa began to deliver two cartons of eggs every 10 days to the local store, who then asked her to deliver more cartons since the demand was greater,” says Jesus Gaspar, a Podemos project technician. “With demand so high and quick success, this led Elsa to consider owning a larger farm.”

Through participation in WE, Elsa and Debora amassed $770 in savings and earned another $645 selling their plastic-woven baskets. By investing a total of $1,415 in their poultry-raising business, the pair grew to owning 265 egg-laying hens that produce an average of 8 to 9 egg cartons a day. Now, Elsa and Debora have expanded their sales to 4 local stores and determine their prices by egg size, earning an average of $5 per carton.

“Now we hope that the profits will be more, and the investment will not be as much as the initial one,” Elsa says. “Now we have our warehouse, and we conduct good production management.”

Although the Podemos project supported Elsa and Debora with their business plan and marketing efforts – helping the duo to create a banner, business cards and profile page on social media – their dedication and commitment to growing their knowledge and skills base is what ultimately helped turn their dream into a reality. Within nine months of their initial investment, they expanded their farm facilities, modernized its management and currently have a net income of $620.

Debora, who is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in entrepreneurship, says it has been invaluable to be able to transfer what she is learning in the classroom to the real-world experience of running a business with her mother.

“For us women, it is very difficult to continue studying. There are not many opportunities in the community,” she says. “I have to travel to the municipality to study, and now I see that my efforts are paying off.”

As Global Communities closes out the Podemos project in Pacate, we leave behind an installed capacity at the community level that has empowered local leaders like Elsa and Debora with the conviction of what they can achieve when given the right resources and support.

“At the beginning, everything seemed like a dream,” Elsa says. “Now, we see that it is possible with the ideas they gave.”

This success story is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Global Communities and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

The post Mother-Daughter Duo Hatch Success with Poultry Farming Business in Rural Guatemala appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post Hygiene Promotion Volunteers Help Make Clean Water Count in Communities appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>Now, more than 80 families – around 380 individuals – are benefiting from a potable water system implemented by Global Communities. The critical infrastructure was built with support from the United States Agency for International Development’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance as part of the Strengthening the Agricultural System of Honduras (HASS) project.

Although access to safe drinking water is important, raising awareness about good hygiene practices is fundamental to the health and well-being of communities. Recognizing this, Global Communities has trained 300 people to serve as hygiene promotion volunteers through HASS.

Following her mother’s example of service to others, Margarita Tejada (42) became a hygiene promoter to make a positive impact in her community. Although she has been doing similar volunteer work for more than two decades, she convinced her husband, Juan José Pérez (46), to join the HASS team of volunteers as well – a first for the security guard.

In addition to teaching neighbors about effective handwashing and other healthy hygiene and sanitation practices, Margarita and Juan José also explain the importance of keeping the community’s new water supply clean and safe. Before the water system was installed, it was challenging to promote these behaviors because drinking water was not readily available. Now, more and more residents of El Bijao are becoming actively involved in community cleaning actions to keep the system in good working order.

Alejandra Fuentes (28) has two children, ages one and six, and expressed admiration for the volunteer work that Margarita, her husband and other hygiene promoters have been doing for the community, noting “they do it from the heart.” She also shared what she has personally learned because of the HASS team’s efforts and how the project has impacted El Bijao as a whole.

“I used to not know about the importance of handwashing so frequently. For example, I didn’t know that we should always wash before breastfeeding a baby, which matters in my case,” Alejandra said. “You can also see that the cases of diarrhea have gone down, or decreased, because children in the community used to get sick very often and now they don’t.”

With support from USAID/BHA, Global Communities has rehabilitated 21 water systems in the departments of Copán, Ocotepeque, La Paz, Valle, Choluteca and El Paraíso, benefiting a total of 11,658 people. In addition, thanks to the efforts of hygiene promotion volunteers such as Margarita and Juan José, more than 17,000 people have received information and education on good hygiene practices and the proper use of water to prevent waterborne diseases.

By gradually raising awareness among residents like Alejandra, Margarita and Juan José have become role models in El Bijao. Their work together shows how the dedication and passion of a few can lead to meaningful improvements in the lives of many.

This success story is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Global Communities and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

The post Hygiene Promotion Volunteers Help Make Clean Water Count in Communities appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post Working to Build Economic Resilience in Guatemala’s Crises-Stricken Highlands appeared first on Global Communities.

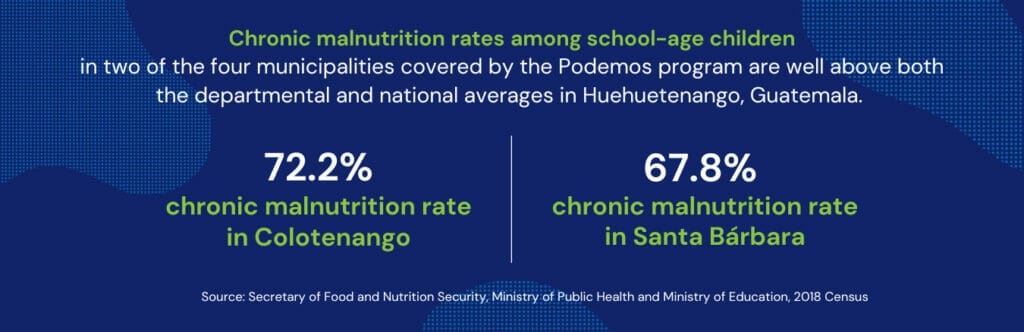

]]>Guatemala’s Western Highlands continue to suffer long-term impacts from widespread destruction caused by Hurricanes Eta and Iota, including the loss of livelihoods and damage to infrastructure and public services. The region is home to a significant portion of Guatemala’s rural population, many of whom rely on subsistence agriculture to survive. Unfortunately, prolonged periods of drought, the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and increasingly severe hurricane seasons have left many families struggling to access nutritious food due to crop failures, lack of income and limited access to markets. High levels of malnutrition among children in the region are of particular concern, with rates of stunting and wasting well above national averages.

With funding from the United States Agency for International Development’s Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA), Global Communities is working to address these challenges and improve food security while also helping families and communities in remote and difficult-to-reach areas build resilience and preparedness for future shocks and stressors.

Through the Podemos program — which means “We Can” in Spanish — we are helping 1,500 households learn how to meet their basic needs, save money and invest in productive assets through economic recovery activities and market systems training. This includes establishing 80 new savings and loans groups in July 2022 that saved $58,000 in their first 9 months.

Because of Podemos, we are making it and learning new things.

Pascuala, Podemos program participant

Eighty more groups were recently formed during the second phase of the program, which began in April. In addition to learning how to save and manage material and economic resources, members are developing valuable leadership skills, building their self-esteem and enhancing social bonds within their groups and communities. Global Communities has also identified 54 families interested in developing and strengthening productive activities or small enterprises through technical assistance from the Podemos program.

Pascuala, 27, lives in Aguacatán, a municipality located in the department of Huehuetenango. She is one of 1,216 locals who joined the first round of new savings and loans groups that were established through the Podemos program and is a member of the Mujeres Trabajadoras group, which means “Working Women” in Spanish. Pascuala explained that the name of the group refers to the fact that its members believe in working to improve their living conditions.

Prior to participating in the Podemos program, Pascuala primarily focused on planting onion and garlic to sell at the local market and earn money for her family. She said she was too afraid to try other types of crops due to a lack of knowledge about what would successfully grow where she lives. Now, with technical assistance from Global Communities, she has learned how to plant parsley, cilantro, celery, nightshade, cauliflower and cabbage. Other program participants have also been encouraged to grow strawberries.

“Because of Podemos, we are making it and we are learning new things,” Pascuala said.

In addition to diversifying her crops, Pascuala has also recognized more opportunities to save through her active participation in the Working Women group. To date, she has accumulated more than $100 in savings, which she plans to use to buy a solar panel. Due to a lack of economic resources, Pascuala’s home does not have electricity, so the solar panel will help improve lighting inside. She also repaid the initial loan she received from her group using profits from the local market and still has 60% of her produce left to sell.

Aside from the economic recovery and market system activities that are underway, Global Communities also plans to help 4,700 households (25,380 people) in meeting their basic needs and enhancing food security through multi-purpose cash assistance delivered via the Podemos program. By October 2023, we will also support 482 families to live in more secure and dignified housing through targeted shelter repairs and upgrades.

The post Working to Build Economic Resilience in Guatemala’s Crises-Stricken Highlands appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post Rebuilding a Sense of Home and Hope in Honduras appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>Martha’s broad and welcoming smile begins to fade as she starts to tell her story.

Originally from a small village in Lempira, in the western region of Honduras, she left her town for the city when she was 18 years old. Now 43, Martha says she was looking for better opportunities and had the desire to grow as a person, start a family and eventually build the home of her dreams.

With hard work and dedication, she managed to buy a 13-square meter plot of land in the Ernesto Dieck community in Villanueva, Cortés, where she built a house of wooden columns and tin roofing for herself and her family. That was eight years ago.

In November 2020, Martha and her three children lost that home and all of their belongings to floods caused by tropical storms Eta and Iota. They were one of many families in the community left homeless by the destruction.

On that fateful night, she recalls being stirred awake by water up to her knees. She immediately fled to the nearest city looking for shelter.

“I only had time to look for the land title,” Martha says. “I couldn’t afford to lose it.”

In response to the crisis, Global Communities arrived at Ernesto Dieck to implement the Honduras Emergency WASH and Shelter (HEWS) program funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA).

Over the course of 14 months (Nov. 2020 – April 2022), the HEWS program aimed to address both the immediate needs and early recovery of 100,050 people by organizing access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene, safe living conditions through improved shelter and settlements, and multi-purpose cash assistance. Program activities also focused on fostering economic recovery through support to agricultural and non-agricultural livelihoods.

Martha and her children were one of 2,378 disaster-affected families to receive temporary shelter/repairs to their damaged homes and latrines to help meet their basic needs as they navigated a new reality. The program also trained interested residents to serve as volunteer community leaders who worked with Global Communities’ field team to organize HEWS activities and convene families for meetings and distributions.

Although I know [this shelter] is temporary, it provides an opportunity to rebuild my goal of having my dream house.”

Martha, HEWS program participant

“This shelter that the project built for us means so much. I feel safe and happy having a dignified roof over my head,” says Martha, who also credits the HEWS program with helping her discover her community leadership capacities.

In addition to assisting HEWS program staff with identifying families in need of support, Martha also serves as treasurer of Ernesto Dieck’s board of trustees. Although she has held this role for the past four years, she says she now feels more secure and confident managing resources thanks to training opportunities offered by Global Communities through the HEWS program.

One of her new goals is to work with government authorities to bring electricity and a stable water supply to the Ernesto Dieck community. She also wants to become president of the board of trustees. As she pursues these new ambitions, Martha says she has not forgotten about the one that first brought her to Ernesto Dieck several years ago and disappeared before her eyes in the wake of the storms.

“Although I know [this shelter] is temporary, it provides an opportunity to rebuild my goal of having my dream house,” she says. “It will be pink on the outside, with concrete walls, everyone with their own room, and a large kitchen to get together to cook our meals.”

In addition to providing over 2,378 disaster-affected families with temporary shelters or shelter repairs following tropical storms Eta and Iota, the HEWS program supported 3,784 farmers in the departments of Valle, Choluteca, El Paraíso, Copán, Ocotepeque and Santa Bárbara to regain their livelihoods. Studies estimate that more than 220,000 acres of crops were damaged by the tropical storms. A severe drought followed that is expected to continue throughout the year, and crop loss is predicted to range between 30 to 50 percent in the Dry Corridor region of Honduras. The HEWS program supported farmers by providing improved seeds, fertilizers and other agricultural inputs as well as training and technical assistance to improve their adoption of new farming techniques.

“The way I see things now, I know I will get ahead,” says Daniel Aguilera, a subsistence farmer from the San Lorenzo community in the department of El Paraíso. “This is an opportunity for us to visualize a better future and transition from subsistence agriculture towards selling our products in the market, thus improving our local economy.”

Global Communities will continue working with farmers like Daniel over the next three years under the Honduras Agricultural System Strengthening (HASS) project, funded by USAID/BHA, which seeks to increase the resilience of subsistence farming communities and ensure they are better prepared to overcome the challenges posed by future shocks.

This content is part of Future Forward, a thought leadership and storytelling series on how Global Communities is driving change to save lives, advance equity and secure strong futures. To learn more, visit globalcommunities.org/futureforward.

The post Rebuilding a Sense of Home and Hope in Honduras appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post Supporting Displaced Livestock Breeders in Northwest Syria appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>While the family was able to bring livestock with them – their only source of income – local economies are in a downturn, causing food prices to skyrocket and the value of Syrian currency to decline. Commercial animal feed is only available in limited quantity, often of uncertain quality and is beyond the purchasing power of most livestock breeders. As a result, Samira has been forced to use more than the usual share of her savings to buy essential fodder for her farm animals. Lack of access to pastures, especially during the winter season, has further exacerbated the challenge.

Without your help, we were planning to sell our livestock for a cheap price as we cannot buy the fodder.

INSPIRE program recipient, Syria

To help meet the emergency food needs of vulnerable families like Samira’s and support household and community food security, Global Communities implemented the Investing in Nutrition in Syria, Promoting Infrastructure and Resources in the Economy (INSPIRE) program.

From June 2019-September 2021, with funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA), INSPIRE supported a total of 508,021 Syrians by distributing monthly food baskets, ready-to-eat rations, bread and kitchen garden kits. The program also assisted with mill and bakery rehabilitation and provided fodder kits to more than 1,000 rural families, curtailing the need for struggling livestock breeders to sell productive animals in order to buy feed and sustain their remaining flocks.

“Without your help, we were planning to sell our livestock for a cheap price as we cannot buy the fodder,” said one recipient of the INSPIRE program. “You saved the livestock by this assistance.”

Since receiving fodder kits and monthly food baskets through INSPIRE, Samira has been able to better stabilize her family’s situation as well. She has noticed an increase in the milk production of her sheep, which enables her to make homemade dairy products to feed her children, freeing up finances she no longer needs to use to buy milk from the local market. With her savings, she was also able to purchase a sewing machine that she uses to bring in additional income.

“I wish to live a decent life with my children,” said Samira, noting her desire to see them complete their education and receive basic health care in the midst of Syria’s ongoing crisis. One of her daughters currently needs eye surgery.

Learn more about how Global Communities is working to help Syrians who have had to flee their homes cope with the enormous demographic shifts that have taken place, adapt to their new lives and livelihoods and build resilience.

The post Supporting Displaced Livestock Breeders in Northwest Syria appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post Emerging Farmers Partnership GDA appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>Zambia’s development holds much promise but faces much peril. Urban economic growth has boomed, however rural areas have stagnated in poverty. Most rural households are engaged in subsistence-level farming on small plots that are not economically viable and often turn to unsustainable livelihoods that degrade natural resources to supplement their incomes.

Although the agriculture sector in Zambia employs close to 66 percent of the total labor force, it contributes only five percent of gross domestic product (GDP), an indication of poor productivity. The Emerging Farmers Partnership aims to transform the agricultural sector and support increased productivity, incomes, and sustainable farming practices for 10,000 emerging Zambian farmers.

Life of Project: October 2020 – October 2023

Geographic Focus: Central, Copperbelt, Eastern, North Western, and Southern Provinces

Chief of Party: TBD

Partner: Global Communities Sub-Partners: Coreva Agriscience and John Deere

Total USAID Funding: $3 million

USAID Contact: Harry Ngoma – [email protected]

Maize is the major staple food crop for Zambian households yet its productivity has been chronically low. This is due to the limited adoption of improved technologies and practices, and vulnerability from reliance on rainfall, which has become more variable due to climate change.

In recent years, the invasion of the Fall armyworm has also threatened food security throughout the region. In addition, traditional practices of preparing the land, weeding, and harvesting require significant manual labor, much of which is provided solely by women. All these challenges result in food insecurity that is primarily affecting rural households.

USAID, John Deere, Corteva Agriscience, and Global Communities have come together to carry out a market-based approach to facilitate the Emerging Farmers Partnership (EFP) project. EFP will catalyze greater productivity of emerging farmers working with 20-60 hectares of land, support their communities, and contribute to building a resilient global food system in Central Province (Mumbwa, Chibombo, Kapiri and Luano), Southern Province (Chikankata, Mazabuka, Monze, Kalomo and Choma), Copperbelt Province (Mpongwe, Lufwanyama and Masaiti), Eastern Province (Petauke), and North-Western Province ( Solwezi and Kasempa).

Youth and women will represent 30 percent of the project’s key beneficiaries, and will be empowered with educational resources, technologies, and access to capital.

While EFP focuses on emerging farmers, it will also contribute to the reduction of rural poverty among smallholder farmers. The emerging farmers will improve the livelihoods of smallholder farmers in their communities by demonstrating improved practices, aggregating offtake, providing tillage and other services, and facilitating input credit.

Expected Results

EFP private sector partners expect to provide $2.2 million in input finance and $35 million in equipment financing to emerging farmers. Approximately 1,000 emerging farmers will receive financing to invest in productive assets, including warehouses, tractors, irrigation and other equipment. An additional 8,000 emerging farmers will receive training support through the partnership.

The post Emerging Farmers Partnership GDA appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>The post ‘Our Harvest’ Project Delivers Food, Hope to Guatemalan Families appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>PCI implements Nuestra Cosecha (“Our Harvest” in Spanish) in partnership with Save the Children and Catholic Relief Services and in coordination with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Agriculture in Guatemala. The project, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture through the Local and Regional Food Aid Procurement program, targets five municipalities in the departments of Huehuetenango, Quiche and Totonicapán.

The risks of food insecurity in the region have Nuestra Cosecha staff and Ministry of Education authorities in Huehuetenango working hand-in-hand around the clock to address the situation within the framework of the country’s school feeding law. The Government of Guatemala requires schools to purchase 50 percent of products for school meals from local smallholder farmers.

In early July, Nuestra Cosecha distributed 3,824 take-home rations in the municipalities of Santa Cruz Barillas and Santa Eulalia, linking five local farmers with 17 schools. Rations included both fresh fruits and vegetables from local farmers (güisquil, potatoes, onions, bananas and potatoes) as well as milk, beans, rice, oil and corn flour from the Ministry of Education.

“I am happy and joyful to receive these bags of vegetables. I was keeping an eye out to make sure the products received were good quality,” said Maria Gaspar, a Parent-Teacher Association (PTA) leader and mother who volunteers at her child’s school. “It was a good thing that PCI delivered the products together with those distributed by the Ministry of Education. Even though the school is closed, children will be able to eat. This will help [with their] education.”

PTAs have faced challenges throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, as the crisis has required them to adopt new safety measures, carefully coordinate product collection and make personalized deliveries of take-home rations. During the first phase of the process, fresh products were received at the school and organized into biodegradable bags. During the second phase, PTA members delivered the food rations to parents.

Take-home rations are an alternative model for delivering food during an emergency. This model has allowed Nuestra Cosecha to maintain relationships with local farmers and support the local economy.

“Under normal conditions, agricultural products are consumed only by students in schools. However, under these circumstances, the food will sustain the entire family,” said Wilman Escobedo, Nuestra Cosecha Project Coordinator. “In this way, the project has expanded its impact.”

Nuestra Cosecha will strengthen the local economy for participating farmer families and their organizational capacity while also providing much-needed food to schoolchildren. Suppliers donated 49 additional food rations to cover children who were not enrolled in schools and thus were not covered by the project.

Undoubtedly, emergencies can serve to validate in a short amount of time whether the strategies being used are effective and appropriate. Nuestra Cosecha has proven to be effective beyond school feeding by strengthening the resilience of rural communities and supporting their quick recovery from emergencies.

The post ‘Our Harvest’ Project Delivers Food, Hope to Guatemalan Families appeared first on Global Communities.

]]>