News > Blog

A Partnership for Peace and Prosperity in Eastern Congo

Published 02/22/2022 by Global Communities

USAID’S Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project brokers a business deal to prevent communal violence and increase incomes for artisanal miners in Maniema province

By Kevin Eze

When Aimé* returned to his family’s mining concession after the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, he found throngs of strangers digging for gold. The area, situated in Kabotshome, in the Maniema province of eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), has a long history involving four Congolese presidents and two Congo wars – all of which Aimé’s family has carefully had to navigate to maintain ownership of their land since buying it in 1996.

Fast forward to 2020, amid a global pandemic and gold rush in DRC, and Aimé’s family was faced with an altogether different challenge on their property. In the family’s absence due to COVID-19, hundreds of artisanal miners overran the mining concession. Artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASM) is particularly widespread in the east and northeast of the country. While 73 percent of the population lives below $1.90 per day, DRC miners can make between $2.70-$3.30 per day. Therefore, an unoccupied mine site with gold-rich ore to dig was a rare and attractive opportunity.

Upon returning to their mining concession, Aimé’s family discovered that the artisanal miners operating there were producing about 10 kilograms (kg) of gold per month. By digging on drilling sites beyond the fringes of the property, they were generating an annual revenue of $8 million. Aimé also noted that the cost of unrefined, unprocessed gold being sold by the artisanal miners from his family’s concession was the same as the price of gold on the international market.

Project Overview

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), in partnership with Global Communities and Levin Sources, launched USAID’s Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project to help the Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in its effort to formalize the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector and attract ethically conscious jewelers.

Deeply disturbed, Aimé asked the artisanal miners to leave the site, but they refused. The group cited how they had formed an artisanal mining cooperative, as required by Congolese law, and expected a section of the mine to be approved by the government as a free artisanal mining zone.

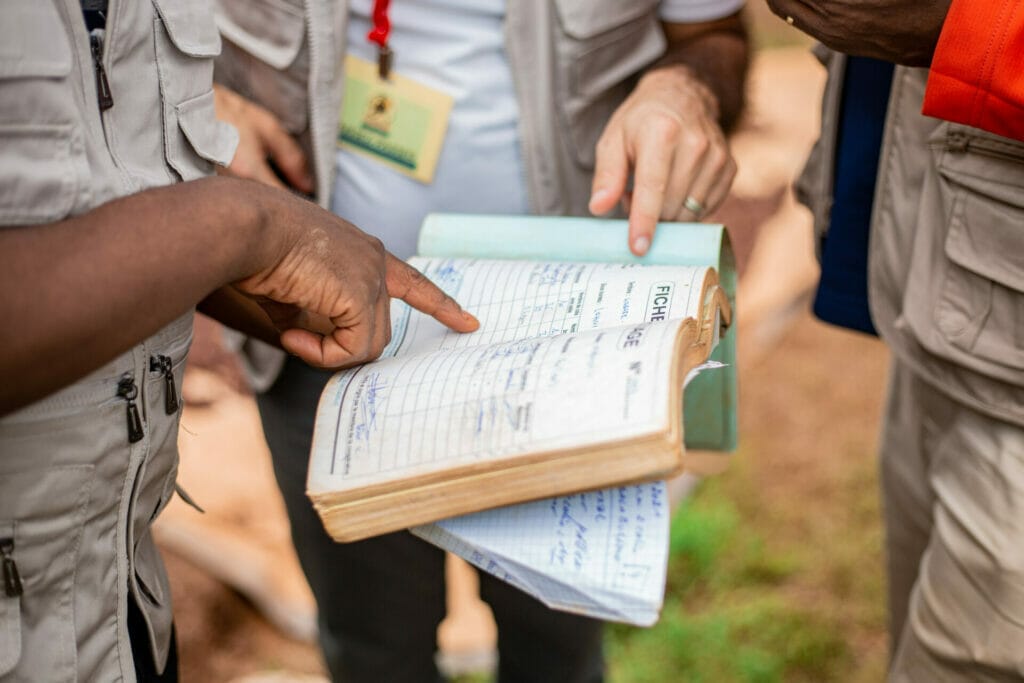

Both parties were unwilling to concede when USAID’s Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project entered the troubled climate. The project team facilitated negotiations between Aimé and the artisanal miners by demonstrating the importance of working together to avoid any conflict that could negatively impact the supply chain. The cooperative agreed to streamline its grouping, structure and mode of operations and, in turn, increase its revenues, thereby ensuring an equitable redistribution of profits among its members. Aimé’s family company, for its part, will gradually regain control of the activities on its site and, based on the working relationship between the parties, continue its exploration plans.

“We opted for a win-win proposal to avoid an all-out conflict. In the last two decades, wars and violence have marked much of the life of ordinary people and their families in this region. We need peace for our businesses to thrive.”

Aimé*, industrial mine owner in DRC

“Previously, the Congolese mining law did not allow industrial miners to deal with artisanal mining, but since 2019 that law has changed,” Aimé said. “For a start, we can employ the artisanal miners as a mining operator contributing to the larger production, benefit from their experience and pay them better salaries.”

Aimé also sees the need for social transformation, as the more gold artisanal miners produce and sell, the more their families seem to experience even greater poverty.

“In 2020 alone, about $5-10 million worth of gold was sold from our site, but one is appalled by what one sees upon a visit to the homes of the artisanal miners,” he said. “The social standing of their communities has not changed; it seems as if nothing has been produced.”

Now, Aimé thinks USAID’s Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project will help them clean up the corridor that maintains ASM and keeps their communities trapped in poverty. He believes that the monthly Corrective Action Plans of the project can help stamp their gold production with a “responsibly sourced” seal and calls it the “first business success.”

However, while being socially conscious, Aimé remembers they also need to make a profit. “This will avert any revolt from the miners,” he said.

Together with the cooperative, his family’s company is now thinking of restructuring ASM, its impact, the proper flow of money and how ASM can bring development — schools, roads and hospitals — to the Kabotshome community.

“We proposed a new business map consisting of who the stakeholders could be to our partner USAID’s Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project,” Aimé said. “That map will help us arrive safe in the port of international clean gold export.”

*All names of individuals in this story have been changed for security reasons.

This success story is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Global Communities and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.