News > Blog

Mothers Take the Center Stage to End Child Marriage

Published 11/26/2023 by Global Communities

By Sushmita Mukherjee, PCI India and Dennis Mello, Global Communities

Proposals for marriage began coming for Pushpa three years ago, when she was only 15 years old. Pushpa felt too young to be married and wanted to continue her studies, something that many girls in Jharkhand – her home region of India – are unable to do.

Jharkhand has some of the highest rates of child and early marriage in India, which exceeded 32% according to the most recent National Family Health Survey. Globally, nearly 1 in 5 girls are married before the age of 18. In some countries this figure is closer to 2 in 5 girls, or 40%, with 12% being wedded prior to the age of 15.

Child, early and forced marriage is a human rights violation and a form of gender-based violence (GBV). Child marriage cuts short girls’ education and obstructs pathways for healthy living, growth and development. It often leads to early pregnancies, which are dangerous for young girls. It also increases the risks of acquiring HIV and experiencing other forms of GBV.

The practice of child marriage is intricately linked to a variety of sociocultural, religious and economic factors, such as poverty, inequality, conflict and barriers to educational opportunities. Each of these factors plays a major role in the communities where child marriage remains stubbornly high despite policy and program efforts designed to prevent it.

Like Pushpa, many girls around the world want education, but have few options beyond becoming wives and mothers. Parents of adolescent girls often face socioeconomic pressures to accept offers of early marriage. And many mothers, like Pushpa’s mother Rukmani, were also married before the age of 18 and had no say in determining their own futures.

Even where laws prohibit child marriage, changing social and gender norms is key to preventing this practice. Mothers can be strong allies in this fight and advocate for girls’ continued education.

Umang: Bringing Normative Change around Child Marriage

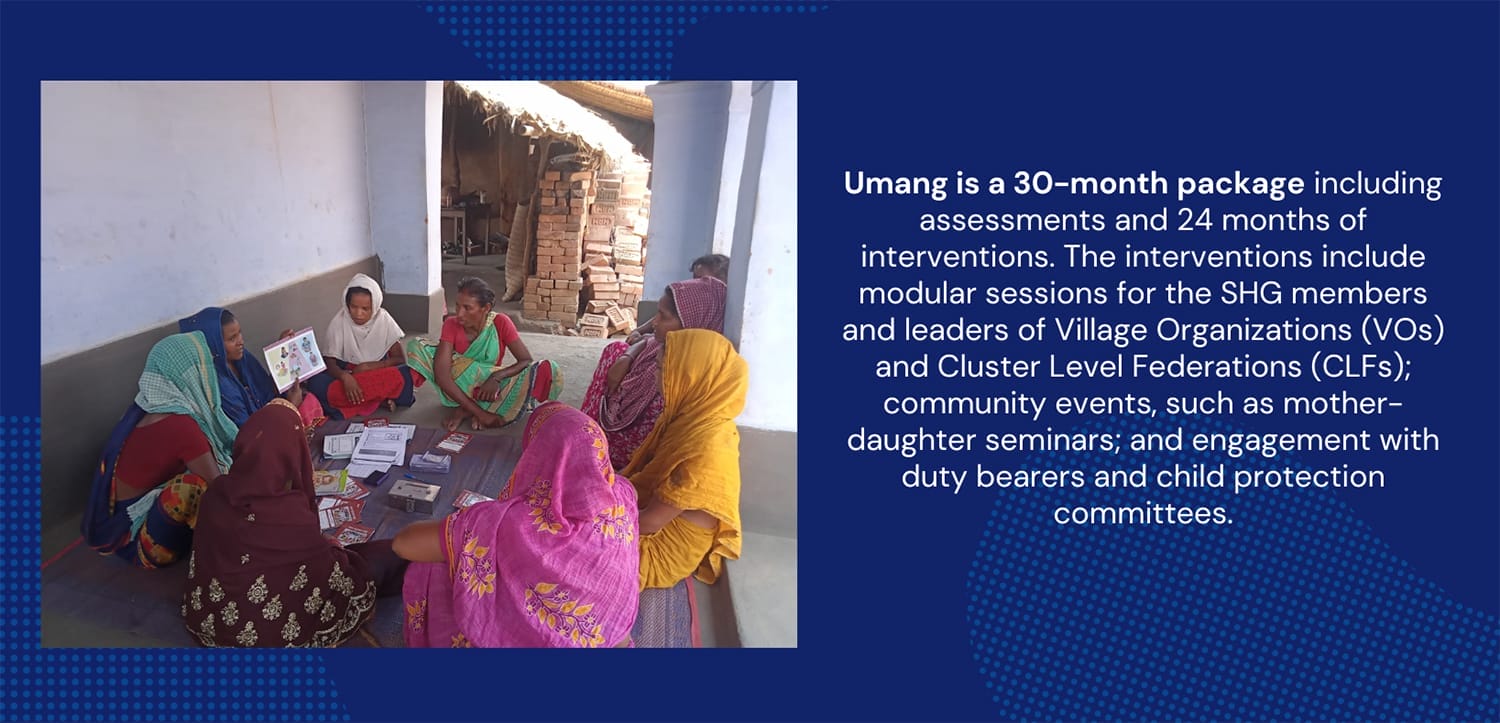

In 2019, Global Communities, in partnership with the International Center for Research on Women, designed the Umang project, which is a comprehensive approach to preventing child and early marriage in Jharkhand, India. The project partnered with the Government of Jharkhand to test the model in two districts, Godda and Jamtara, and is now implemented by PCI India, an independent organization created by Global Communities in the spirit of locally led development.

Umang is a women-led, norm shifting intervention, where women collectives play the central role in molding household and community attitudes away from marrying adolescent girls.

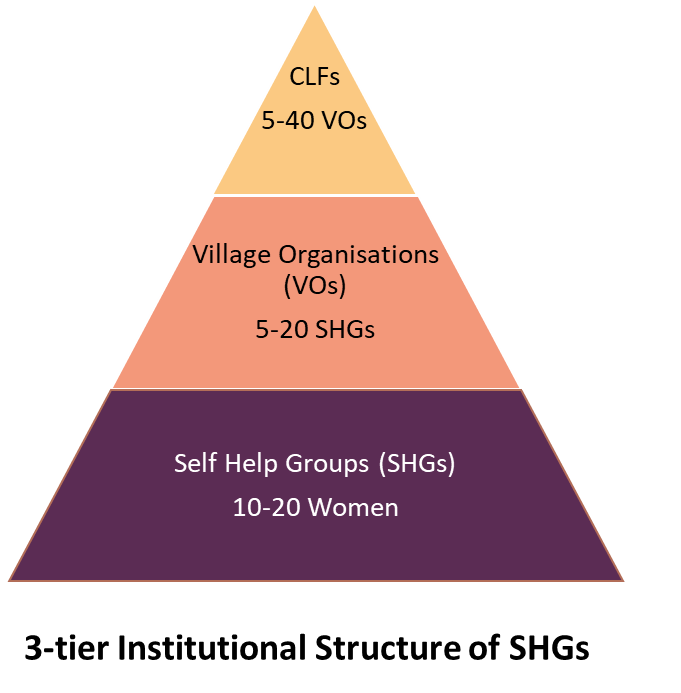

The Umang project works with women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs), which are supported by the Government of Jharkhand and provide a powerful platform for women to discuss their ideas and strategic interests. Women engaged in SHGs often design collective action plans to challenge various harmful practices, such as child marriage.

Supported by Umang, SHG members learn different communication skills to meaningfully participate in discussions and decision-making processes to delay marriages in their communities. Umang strengthens the bonds between mothers and daughters, helping the girls to fulfill their aspirations.

Two women reached by Umang were Rukmani and Pushpa’s aunt Vimla, who both supported Pushpa’s continued education.

I had never considered myself worthy of taking decisions or going against social practices. But project Umang made me realize the difference I can make as a mother.

Rukmani, Umang participant, Pushpa’s mother

Umang brings mothers to the center stage, as they are well placed to effect change and advocate for the betterment of their daughters. Many of these women are survivors of harmful social practices, too: 85% of mothers who participated in Umang could not make decisions about their own marriages, 75% were married before the age of 18, 40% had their first child as children, and 54% never attended school.

Between February 2021 and March 2023, PCI India and its partners conducted an evaluation of Umang, which showed the following results:

- Girls’ belief in their ability to resist marriage pressure increased from 77% at baseline to 95% at endline;

- Girls expressed increased aspirations to study through 12th grade, from 78 to 87%;

- Girls’ confidence in their ability to complete education spiked from 60 to 75%;

- Girls’ belief that they should only work if their in-laws and husbands allow them dropped from 63 to 54%;

- Mothers’ reservations against sending their daughters for higher education and fear of delaying marriage decreased from 17 to 12%;

- The number of girls who faced pressure from parents to end education early decreased from 22 to 15%.

Umang’s design is layered upon the socio-ecosystem of the lives of women and girls. Its main success lies in women’s leadership.

Thanks to Umang, women now negotiate with their husbands and others, often successfully, to delay marriage and continue education of adolescent girls. Moreover, women leaders engage with government officials to demand quality services so that adolescent girls can pursue higher education.

Finally, Umang enables women leaders to provide community-based counseling services to girls and their parents so that they can learn about the harmful aspects of child marriage, the value of education and possible career opportunities. Counseling both girls and their parents ensures there is coordination within the family to support their daughters’ aspirations.

Pushpa is now 18 years old and will soon complete 12th grade. She is planning to continue her studies. Her mother is her biggest champion, ready to invest more in her education. Since 2019, Umang has reached more than 60,000 mothers of school-aged girls in Godda and Jamtara. The project team is working with the Government of Jharkhand to expand the work across 11 additional districts in the state to support the empowerment of many more mothers and adolescent girls.